The Africa Report

Tuesday July 3, 2018

By Tom Gardner

How Abiy handles his relationship with Abdi Iley, the powerful leader

of Ethiopia’s Somali Region, has implications for the country’s fragile

system of ethnic federalism

Somali Regional State

(SRS), Ethiopia’s second-largest region and home to its third most

populous ethnic group, is at a crossroads. The secessionist Ogaden

National Liberation Front (ONLF) had been almost entirely defeated, but

SRS is still, in the eyes of many Ethiopians, a byword for violence and

lawlessness. “From the centre, Somali Region is seen as a wilderness,”

says Fekadu Adugna, an academic at Addis Ababa University (AAU).

Last

year, SRS’s long-standing tensions with the neighbouring region of

Oromia, home to Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group, the Oromo, erupted on

an unprecedented scale. Amidst fighting between regional security

forces, hundreds lost their lives and approximately one million

civilians fled their homes. In the SRS capital of Jijiga, thousands of

Oromos were herded into trucks by police and removed from the city. Many

have not returned. Somalis, meanwhile, flooded back the other way.

Dealing

with the legacy of the violence will be one of the most sensitive – and

urgent – tasks for Ethiopia’s new prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, who was

sworn in on 2 April and is the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary

Democratic Front (EPRDF)’s first Oromo leader in its 30-year history. At

the heart of this task is his relationship with SRS president Abdi

Mohamed Omar – known as Abdi Iley, ‘the one-eyed’. Abdi is one of the

most powerful Somali leaders in the Horn of Africa. Over the past

decade, he has acquired an authority unprecedented in the region’s

recent history.

Hot-footing it to Jijiga

Both

men hail from traditionally marginalised regions with secessionist

histories, and both represent constituencies eyeing greater power at the

centre. But last year’s violence fuelled mutual mistrust, especially a

suspicion among Oromos that Abdi is too close to the Tigrayan People’s

Liberation Front (TPLF), which dominated Ethiopian politics, as well as

the security apparatus, for much of the past three decades. Some in

Oromia and elsewhere hope that the decline of the TPLF heralded by

Abiy’s appointment might spell the end of Abdi, too.

Prime

Minister Abiy’s decision to visit the SRS capital, Jijiga, on 7 April,

as his first official trip, was thus symbolic. It was a bid to calm

nerves in a region anxious once again about its fate in the hands of

distant authorities in Addis Ababa, and fearful of what an Oromo prime

minister might mean for Somalis. On a stage in Jijiga, Abiy and Abdi,

who is said to have been deeply unhappy about the latter’s appointment,

shook hands and promised peace between the two regions.

Bringing

change to SRS will be Abiy’s “litmus test”, says Abdifatah Mohamud

Hassan, former vice-president of the region, now in exile in Addis

Ababa. “It is the epicentre of all the problems in the country”. The

region is unique but in some respects it is Ethiopia in miniature: a

Gordian knot of poverty, authoritarianism, corruption, and ethnic and

clan rivalries.

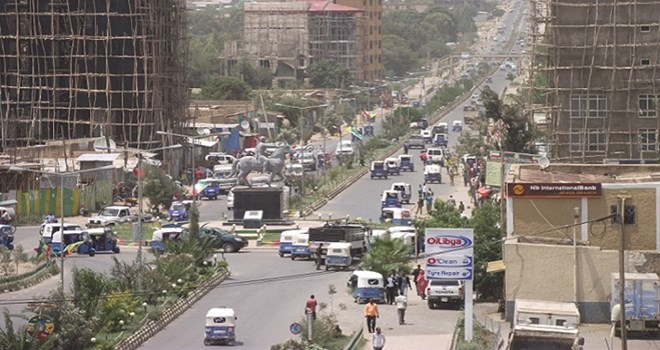

Understanding SRS’s future means

taking a look at its past. For this, the central statue in Jijiga offers

some clues. Unveiled in 2013 by Abdi, it depicts Sayyid Mohammed

Abdullah Hassan, a turn-of-the-century warlord, poet and cleric known to

the British as the ‘Mad Mullah’ and to Somalis as the father of Somali

nationalism. Hassan resisted not only the invading British and Italians

but also the then Ethiopian empire. The monument is a reminder that,

more than a century later, SRS remains a land of conflicting loyalties.

Successive

regimes in Addis Ababa have sought to incorporate SRS, or ‘the Ogaden’

as it is still widely known, into the Ethiopian state, with mixed

fortunes. Before the neighbouring country of Somalia’s government

collapsed in 1991, Mogadishu had claimed the region as part of ‘Greater

Somalia’, and a bloody war was fought between the two neighbours between

1977 and 1978. The separatist ONLF insurgency emerged from the ashes of

Somalia’s defeat. By the late 1990s, it was waging all-out-war against

the EPRDF, a multiethnic coalition that seized power in Addis Ababa in

1991.

But a counterinsurgency campaign launched

after a deadly ONLF attack on a Chinese oil exploration camp in 2007

brought a measure of stability. “People used not to be able to travel

because of war,” says Mohammed Ali, a 24 year-old school administrator.

“But now you can go anywhere.” Ermias Gebreselassie, a lecturer in

journalism at Jijiga University, which opened in 2007, says that when he

arrived in the region 10 years ago it was “almost a war zone”. He

recalls “bombings everywhere” and an environment that was “very, very

hostile. You couldn’t move around at night without being harassed by the

police.”

Diaspora returnees

Today

locals also point to belated signs of economic development. Between

1994 and 2007, SRS had the country’s lowest economic outcomes and

experienced the fewest improvements. Even today, its school enrolment

rates are the lowest in the country. But now members of the Somali

diaspora, such as Hafsa Mohamed, a US-Canadian who runs a local

non-governmental organisation (NGO), are beginning to return home. There

are now three airports, better hospitals and paved roads. A

better-educated, younger generation is increasingly taking up posts in

regional offices.

Until relatively recently, the

region had almost no government. Clan rivalries and endless meddling by

the authorities in Addis Ababa ensured the region churned through nine

presidents from three different political parties in the two decades

after its creation. Such was the political paralysis that, in the early

2000s, a chain was drawn across the entrance to the administration

compound in Jijiga to keep vagrants from squatting in the buildings.

Now

the administration is centred on an imposing palace overlooking the

city, surrounded by freshly manicured gardens. “There’s been an

improvement in the past five or six years,” says Hallelujah Lulie, a

political analyst in Addis Ababa. “They’ve started building a state

structure modelled on highland Ethiopia.”

Abdi

Iley has been key to this. A member of the Ogadeni clan, the largest in

SRS, Abdi was regional security chief from 2005, and, unlike many of his

predecessors, was prepared to work with the Ethiopian state while at

the same time championing Somali nationalism. This had the effect of

neutralising the ONLF while winning him a following among his fellow

Ogadenis. “After Abdi came to power, he removed the bandits from the

region,” says Abdo Hilow Hassan, a lecturer in journalism at Jijiga

University. “And it has been at peace.”

But it is

an uneasy sort of peace. The counterinsurgency campaign of the late

2000s was effective but also brutal. A June 2008 report by the NGO Human

Rights Watch found that the Ethiopian National Defence Force and the

ONLF committed war crimes in the Somali Region between mid-2007 and

early 2008.

Abdi, aided by the federal

authorities, established a special police force known as the Liyu, who

continued to report to him directly even after he became president in

2010. Members of the 40,000-strong outfit have been implicated in

extrajudicial killings, torture, rape and violence against civilians.

“It’s a state within a state,” says Abdiwasa Bade, an academic at AAU.

“They [the Liyu] will only listen to Abdi Iley.”

The

Ethiopian government’s approach has been likened, by government

officials and outside observers alike, to Vladimir Putin’s

counterinsurgency strategy in Chechnya: handing a local strongman

resources, state power and unprecedented autonomy in exchange for

stability.

Abdi’s fiefdom

The

price of stability is extreme authoritarianism. When, in 2015,

anti-government protests erupted across Oromia and Amhara, SRS was

quiet. Locals in Jijiga laugh at the idea of protests against Abdi’s

rule – though there have been sporadic demonstrations in parts of the

region dominated by non-Ogadeni clans since April. Abdi’s critics refer

to the region as a ‘fiefdom’ in which all power is concentrated in the

hands of the president and his family.

“For the

last 10 years, people have not been safe,” says a local teacher, who

claims he was arrested and beaten twice, and who asked not to be named.

“There is collective punishment. If one person speaks out, the whole

family will be arrested and punished.” He continues: “Why is the federal

government quiet about these things? […] I feel like it’s two different

countries: you can be safe in Addis Ababa, but you are not safe here.”

Many

of these dynamics coalesced in last year’s conflict with Oromia. The

border between the two regions has been contested– often bloodily –

since the introduction of ethnic federalism in 1995. Members of both

regions have a history of seizing land and resources from each other,

often with the backing of local politicians. Last year, violence took on

a worrying new dimension, as regional security forces engaged in open

warfare. Each side blamed the other for the dramatic upsurge in

bloodshed.

Oromos pinned the blame squarely on

Abdi and the Liyu. Many pointed to the SRS president’s close links with

generals in the federal military, and argued that the failure of the

federal authorities to intervene was evidence of political involvement

at the upper-echelons of government.

Even outside

Oromia, many argue the conflict was deliberately engineered to weaken

the region’s new leaders, notably Abiy and Oromia president Lemma

Megersa, who were then clamouring for more power. As for Abdi, his

economic clout is underpinned by the flows of contraband commerce that

run through his region. Some people say he acted in order to halt

efforts by Oromo authorities to disrupt the smuggling routes he and his

allies rely on. When violence escalated and Addis Ababa stayed mostly

silent, it seemed a blind eye had been turned once again to Abdi’s

excesses.

But leaders in Oromia also share part

of the blame, not least since atrocities went unpunished on both sides.

Indeed, for many ordinary Somalis, the little attention paid to victims

on their side, of whom there were also many thousands, merely highlights

their relative invisibility in Ethiopian public life. “I feel like the

Oromo narrative is quite dominant,” says Hafsa, the returnee who last

year met with Somali women who had been brutally attacked and sexually

assaulted by Oromo men. “Somalis are often criminalised in this

particular conflict. It seemed like only Oromos were victims, even

though both sides had victims.”

Abiy’s subsequent

election and the rise of his Oromo faction to pre-eminence within the

multiethnic EPRDF sparked fears of a backlash against Somalis. “People

worried he would punish us,” says Abdo, the Jijiga University lecturer,

though he adds that such anxieties have been largely quelled since the

prime minister’s visit to the region. But how long will the truce last?

Federal conundrum

Abiy’s

room for manoeuvre is limited. Any attempt to tame Abdi’s autonomy will

likely be met with stiff resistance. His power to remove elected

regional officials is limited. Efforts to reform or even disband the

Liyu security force would face similar constitutional hurdles, and in

any case would be politically difficult without tackling the special

police that operate in other regions at the same time. Moreover,

reforming the federal security apparatus in SRS will depend largely on

the extent to which the new prime minister manages to assert his control

over the entire military hierarchy.

Even more

vexing, though, is the age-old challenge of turning SRS into a fully

paid-up member of the Ethiopian federal state. On one level, this may

mean doing away with the second-tier status of the Somali People’s

Democratic Party within the EPRDF. Unlike the coalition’s four main

constituent parties, the Somali faction is merely an ‘affiliated’

grouping, a legacy of deep-seated prejudices against Ethiopia’s

nomadic populations. One consequence of this is that Somalis remain

woefully underrepresented in the federal government: Abiy’s cabinet has

only two Somali ministers.

That might change as

Ethiopian Somalis slowly become more assertive. “If we continue like

this, one day we will lead Ethiopia,” says Abdo, the Jijiga University

lecturer. “We’ve had a Tigrayan, a Southerner and an Oromo prime

minister. Why can’t we have a Somali prime minister one day?”

This article first appeared in the June 2018 print edition of The Africa Report magazine