By Jehan Casinader

Sunday October 11, 2020

Asha Ali Abdille was released from prison in February 2017 after serving all of the nine-year jail term she received.DAVID HALLETT/STUFF

Asha Abdille was New Zealand’s first convicted plane hijacker. A decade on, has she been failed by the mental health system? Jehan Casinader investigates.

Asha Abdille has spent much of her life grasping for freedom.

A desire for freedom led her to escape Somalia during a bloody civil war. Freedom beckoned in New Zealand, where she arrived – alone – as a teenage refugee hoping to build a new life.

And freedom was on Abdille’s mind when, on a summer morning in 2008, she tried to hijack a plane.

At Blenheim Airport, she boarded NZ2279 with six other passengers. They were travelling to Christchurch on a tiny aircraft.Shortly after takeoff, the woman in seat 1A approached the cockpit with a knife, and demanded that the flight was diverted to Australia.

The two pilots made a mayday call as they tried to calm Abdille, who interfered with the control panel. There was a skirmish. The captain’s hand was badly cut, and a passenger’s hand was also injured.

After a frenzied 26 minutes in the air, the plane made an emergency landing in Christchurch. Passengers escaped through the rear door, before Abdille told the pilots, “It’s just you and me now”.

One of the men wrestled the knife from her, but his foot was cut. Police swarmed the aircraft, dragged the 33-year-old from the plane and forced her onto the tarmac in handcuffs.

Air National Jetstream plane, which landed in Christchurch after being hijacked by Asha Abdille on February 8, 2008.JOHN MCCOMBE

The event was shocking – and novel. It was the first hijacking in New Zealand’s domestic aviation history.News stories referred to Abdille as a “crazed, knife-wielding woman”. Her identity as a Somali refugee was a big focus of the coverage. She was jailed for nine years, and completed her full sentence.

Today, Abdille is still chasing freedom. She is detained in a forensic mental health unit in Porirua, with almost no contact with the outside world.

Her life is marked by isolation – and desperation.

Many years before she tried to hijack a plane, Abdille made a mayday call of her own.

Asha Abdille is detained in a forensic mental health unit in Porirua, with almost no contact with the outside world. KATHRYN GEORGE/STUFF

Asha Abdille knows that this article is being written about her, and she wanted to participate in it. But Capital and Coast DHB, which is responsible for Abdille’s care, declined Stuff’s request to meet her.Guled Mire, a Somali community leader and Fulbright scholar, is willing to speak on Abdille’s behalf. He has spent time with her in recent months.

“Asha has wanted to tell her full story for a very long time,” says Mire. “I don’t think the media or the public were interested. But when you look beyond the headlines, you realise that our society has utterly failed this woman.”

Abdille was born in Warder, a Somali region of modern-day Ethiopia, in a family of 17 children. She did not receive a formal education, and began working as a housemaid at the age of 10 in order to provide for her family.

She was in her mid-teens when the Somali civil war broke out, and says she fled the violence after becoming separated from her relatives.

Along with thousands of displaced people, Abdille walked for days until she reached a refugee camp in neighbouring Kenya. She was violently attacked and sustained severe head injuries, before being airlifted to Nairobi for treatment.

From there, she was granted refugee status in New Zealand, as part of the first wave of African refugees accepted by this country. When she came here in 1994, Abdille was 19 years old.

“Arriving in a new country is not easy, let alone when you are young, black, female, single and visibly Muslim,” says Mire. “She stuck out, she did not speak English and did not have any family here.”

Back then, new refugees did not receive full psychiatric assessments, and were provided with little mental health support.

Abdille claims she was sexually assaulted by a support worker who was involved in her resettlement.

Two years after arriving, she told a TV reporter that she spent the nights crying, and had been unable to adjust to Kiwi life.

“It's very hard,” she told The Dominion Post in 2004. “From when I come to this country in 1994 up to now, I didn't settle properly like everyone else. I'm alone.”

Abdille was desperate to be reunited with her family, and hoped they could also be granted refugee status. She picked fruit, borrowed money from friends and sold her furniture to pay for her relatives to get the necessary paperwork. Her deaf sister was allowed to come to New Zealand, but the rest of her family was not.

“Evidence shows that when you keep refugee families together, that gives them the best chance of integrating into society,” Mire says. “That did not happen for Asha.”

In the early 2000s, her mental state began to unravel and her behaviour became erratic. She was accused of throwing faeces on a police officer and threatening to pour petrol on a Red Cross worker. Abdille racked up 27 convictions, including for violence and intimidation.

Zeenah Adam is a Muslim clinical psychologist in Wellington. She says the vast majority of refugees have a smooth transition to New Zealand life, but a few face greater challenges because of the trauma they have experienced.

“Trauma can lead people to become hyper-responsive to anything that resembles a threat – whether that threat is real or not,” she says. “It affects how people think and reason, and how they regulate their emotions.”

Adam is not involved in Abdille’s case, but says undetected trauma can contribute to criminal offending.

“If [Abdille] has continued to feel isolated, unsupported and trapped, her behaviour may be driven by an extreme sense of fear, rather than a desire to cause harm to others.”

In 2004, Abdille shared with the Dominion Post her desperation to be reunited with family.ANDREW GORRIE/STUFF

You’d be forgiven for thinking Abdille came to prominence when she hijacked the plane. In reality, she became known four years earlier, when Winston Peters disparaged her in Parliament’s debating chamber.In November 2004, Peters used Abdille’s story to attack the refugee system. He said she was a “sympathy case for bleeding-heart liberals”, and that she had “a background that Al Capone would have been proud of”.

The New Zealand First leader questioned Abdille’s refugee status, and claimed she had spent “10 years bludging off the New Zealand taxpayer”.

Guled Mire says Peters’ comments show that Abdille’s mental health issues had been “politicised long before she tried to hijack a plane”. She was also shunned by Somali Kiwis.

“In the Somali language, there is no word for mental distress,” Mire explains. “The only word that exists is ‘waali’, which literally translates as ‘crazy’. That causes stigma.

“Asha’s issues were well-known within the Somali community, and people ostracised her. So, not only was she excluded from wider society, she was excluded from her own community.”

In 2008, Abdille reached breaking point. She attempted to hijack a plane, hoping to divert it to Australia. From there, she wanted to travel home to Somalia.

Abdille pleaded guilty. The judge noted that she had led a “very troubled and unhappy life”, and was suffering from chronic post-traumatic stress disorder and depression at the time of the incident. Even so, she was jailed.

In prison, Abdille says she was assaulted. She successfully made a claim against the Department of Corrections and was awarded compensation, some of which was distributed to the victims of her hijack attempt.

By February 2017, she had completed her full nine-year sentence. At her final hearing, the Parole Board noted that Abdille had previously threatened to hijack another plane and set herself on fire.

There was no plan to return her to the community. But she could not be kept in the justice system, because she had done her time.

Officials decided to use a little-known tool in the Mental Health Act: a “restricted patient” order. It allows them to indefinitely detain someone who presents “special difficulties” because of the danger they pose to others.

Professor Warren Brookbanks, a criminal and mental health law expert at AUT, says these orders are useful in difficult cases.

“There are people whose behaviour represents a higher level of risk to the public, and therefore warrants a higher level of security,” he says.

Around four Kiwis are under a “restricted patient” order.

Since 2017, Abdille has been detained in a medium-security forensic mental health ward in Porirua.

She lives in a small single room and can access a common area with other patients, but cannot move anywhere in the grounds without supervision. She receives psychiatric medication.

Abdille’s phone calls are monitored, and she does not have free access to the internet. The only people who visit are her lawyers and advocates.

“Nobody will be wanting to see her detained as a long-term institutionalised patient,” says Brookbanks. “The primary aim should be to give her the treatment she needs, with the end goal of releasing her back into the community to live as a normal person.”

Asha Abdille is detained in a forensic mental health unit in Porirua, with almost no contact with the outside world.KATHRYN GEORGE/STUFF

But documents obtained by Stuff raise questions about whether Abdille is being given the best chance of recovery.In March 2019, she had an altercation with another patient, sparked by a disagreement over the use of a communal shower. Abdille became loud and abusive.

She was placed into a “de-escalation” room that is used to stabilise a patient’s behaviour. Typically, they may stay there for a few days. Abdille was kept there for more than three months.

She complained to the District Inspectors, a watchdog group of independent lawyers appointed by the Government. They ensure that patients’ rights are upheld.

In a lengthy investigation, the inspectors found Abdille was kept in a “small locked area” for three months, often with no contact with other people, except staff.

Her treatment had “many of the hallmarks of seclusion”, the inspectors wrote. The unit was cold, and some of its conditions “fell below an acceptable standard”.

Abdille’s lawyer, Charlotte Kerr, says this is a compelling example of the kind of treatment her client has received. It feeds into Abdille’s long-held belief that the system is against her, and prevents her from making progress.

“For Asha, being in hospital is worse than the prison environment, where she could see the end [of her sentence],” says Kerr. “At the moment, there is no foreseeable future for her outside a hospital setting.”

In June 2020, the District Inspectors made a swathe of recommendations to Capital and Coast DHB. They said Abdille should receive trauma counselling. They also want her to have more interaction with people outside the facility.

A Somali perspective had not been incorporated into Abdille’s treatment – a “significant oversight”, according to the Inspectors. They recommended cultural awareness training for all staff, and for a Somali psychiatrist or psychologist to be involved in Abdille’s care.

Zeenah Adam says it is important that refugees receive “culturally responsive” treatment.

“In collectivist cultures, a person’s mental health is strongly linked to their community,” she says. “Connection to the land is also really important. For someone who has been displaced and feels isolated, that can have a real impact on their wellbeing.”

For Muslims, she says faith-based practices can provide a sense of purpose and meaning, despite the challenges a person faces.

“To deny someone the opportunity to have their culture and faith as part of their treatment plan is to deny a huge part of their identity. In those circumstances, it is unrealistic to expect them to get well.”

What about Abdille’s “restricted patient” status? Does she pose a greater risk to the public than other mental health patients?

Her lawyer says the attempted hijacking in 2008 was a one-off.

“Asha explains that she is really sorry about what she did,” says Kerr. “She has expressed remorse to me. She was incredibly distressed at the time, and was desperate to get back to Somalia. She has no intention of hijacking a plane ever again.”

Abdille still wants to return to her homeland, because she can’t see a future for herself in New Zealand. But Kerr says the “restricted patient” label is preventing her client from accepting the treatment she needs.

“She feels so persecuted by the system that she doesn’t want to engage with her treatment providers,” Kerr says.

In their report, the District Inspectors acknowledged that Abdille can be a challenging patient, and is sometimes “aggressive and hostile”. She has complex psychiatric issues.

But the Inspectors urged the DHB to work harder – and more urgently – to allow Abdille to lose her “restricted patient” status, ideally within 12 months.

“No one is saying that Asha should be released into the community right now,” says Guled Mire. “She’s not ready for that. But the condition she is currently held in does not benefit anyone. It’s like locking her up and throwing away the key.”

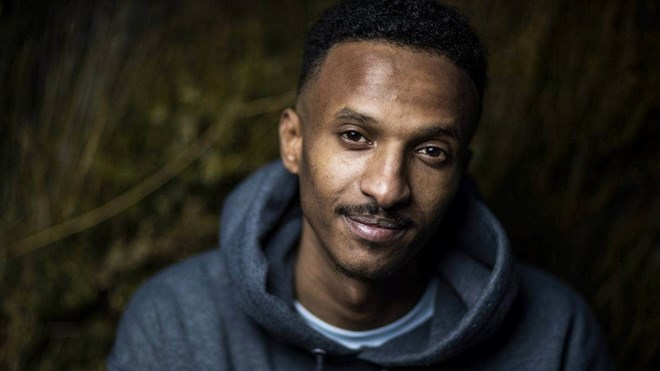

Guled Mire is an advocate for Abdille.ROBERT KITCHIN/STUFF

Mire says the Somali community is willing to be involved in Abdille’s rehabilitation.“Asha does not see herself as mentally unwell, but she knows there are challenges she needs to overcome, and she wants to do that.”

Capital and Coast DHB and the Ministry of Health refused to comment on Abdille’s case, citing privacy concerns. But they affirmed the quality of care in their facilities. The Ministry said it is considering the District Inspectors’ recommendations.

One option is for Abdille to be transferred to another city and DHB, so that she can begin a fresh relationship with a new treating team.

In the meantime, she remains in a forensic unit in Porirua, where she participates in an art group, earns a little money from gardening and cooking, and reads books about women’s issues. Abdille has begun writing her own story, and hopes to publish it one day.

Over the past year, she has been taken on occasional outings – escorted by three nurses. On one trip, she went to the post office to get a new ID. On another, she visited The Warehouse to buy trainers. Each trip went without incident.

These are glimpses of the life she could have again, one day.

Mire says Abdille’s case symbolises many issues facing modern New Zealand, including the need for mental health reform, and the social exclusion faced by minority groups.

“After the Christchurch terror attack, there has been a lot of talk about how we need to stop treating our Muslim community as if they are a threat to society,” he says. “Now is the time to call out the injustice that Asha is facing.”

At the heart of Abdille’s case, there is one central question. Is she is a prisoner of her own mind, or a prisoner of a system that has destined her to stay in a mental health facility for the rest of her life? The answer is elusive.

But in their report, the District Inspectors used six words that neatly sum up Abdille’s predicament.

“She feels powerless,” they wrote. “And she is.”