By GIULIA PARAVICINI, DAWIT ENDESHAW

and KATHARINE HOURELD

Sunday May 9, 2021

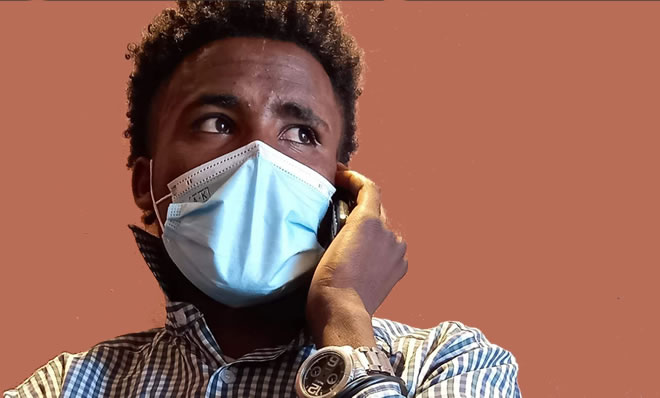

Street trader Nigusu Mahari, an ethnnic Tigrayan, was arrested last year. REUTERS/Stringer

Police arrested Tigrayan street trader Nigusu Mahari last year as he strolled along the traffic-clogged streets of Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa. He says he was speaking on the phone in the language of his homeland, a distant region in the north.

Officers accused the broom hawker of planning a bombing, trying to overturn the constitution and working with Tigrayan rebel fighters. Nigusu professed his innocence. Six weeks later, a judge released him on bail without charge, court records show, after Reuters began inquiring about his case.

Nigusu is among thousands of Tigrayans swept up in a nationwide crackdown that started last November, when fighting erupted in Tigray between federal forces and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the party that dominated the national government until three years ago. Tigrayans themselves are a small minority in Ethiopia’s mosaic of more than 90 ethnic groups and nationalities.

“They arrested me from the street because I spoke Tigrinya,” Nigusu, 25, told Reuters. He said he was just one of three dozen from his home region in the same jail. “I saw 35 Tigrayans, and I told myself that this is not about the TPLF. It’s about the Tigrayan people.”

Authorities did not respond to questions about Nigusu’s case. Federal police spokesman Jeylan Abdi told Reuters that if innocent people are detained, they are swiftly released. Police have caught many TPLF supporters “red-handed with firearms and ammunition,” he wrote in a text message.

Tigrayans say the government’s efforts to crush a TPLF rebellion have unleashed an ethnic witch hunt against them. Across the country, Tigrayans have been arrested, harassed, sacked or suspended from their jobs, or had their bank accounts temporarily frozen, according to bank records, letters from employers and interviews with government officials, rights groups and lawyers.

Reuters spoke to more than two dozen Tigrayans who said their careers and personal lives have been upended because of their ethnicity. They included families of Tigrayan soldiers who’ve been rounded up and put in detention camps; Tigrayan diplomats dismissed or suspended from their postings; academics barred by their universities from lecturing; Tigrayan civilians who say they were arbitrarily detained, and Tigrayan peacekeepers who sought asylum in South Sudan, fearing arrest if they returned home. Most spoke on condition of anonymity, citing concerns over their safety.

The allegations come in the wake of reports of major rights abuses in Tigray – including mass killings of civilians and gang rapes of Tigrayan women. In April, Reuters detailed accounts of women tortured and raped in conditions that a regional official described for the first time as “sexual slavery.”

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, whose parents are from Ethiopia’s two biggest ethnic communities, has stressed that his government’s fight is with the TPLF and has called on his countrymen not to discriminate against Tigrayans as a group. His spokeswoman, Billene Seyoum, told Reuters the prime minister “spearheads a vision of a united Ethiopia with zero tolerance for discrimination based on ethnic identity.” To insinuate that suspects are arrested because of their ethnicity “is interfering in upholding the rule of law and purposely fomenting divisions,” she added.

Attorney General Gedion Timothewos said there was no government policy to “purge” Tigrayan officials. He conceded, however, that some state organizations “may have overestimated their exposure or vulnerability” to penetration by the TPLF.

“The TPLF had a huge network in Addis, so we had to err on the side of caution,” Gedion said. “I would not rule out that innocent people might be caught up in this situation.”

The at times heavy-handed response is fueling Tigrayan anger and complicating Abiy’s efforts to end the conflict in Tigray. Thousands of people have been killed and more than 1.7 million displaced.

Fighting started on Nov. 4 when, according to the government, forces loyal to the TPLF, the then-governing party in Tigray, attacked army bases in the region. The violence followed months of deteriorating relations between the TPLF and the federal government over what the party sees as discrimination against Tigrayans and attempts to centralise power – accusations the government rejects. A TPLF spokesman has denied that the group made the first strike.

Tigray is the most dramatic example of ethnic and regional tensions that are surfacing across Ethiopia, imperilling the multiethnic democracy of Africa’s second-most populous nation and a regional linchpin. Ethiopia hosts the African Union headquarters. Its security services work closely with Western intelligence against Islamist extremists. And its peacekeepers serve in Somalia, Sudan and South Sudan. More than 60,000 Tigrayan refugees have fled into neighbouring Sudan, where a long-simmering border dispute is heating up.

“With the conflict in Tigray set to continue, and many people there supporting armed resistance and even secession, the pressing challenge for the prime minister is holding the country together rather than how to further unify it,” said William Davison, an Ethiopia analyst at the International Crisis Group, a research organization that seeks to prevent deadly conflicts.