Sea food Source

Tuesday November 2, 2021

Uncertainty has gripped the coastal fishing communities in Kenya after a ruling by the United Nations International Court of Justice (ICJ) and largely agreed with Somalia’s claim of ownership of a huge chunk of offshore area that served as a key fishing ground for the past 35 years.

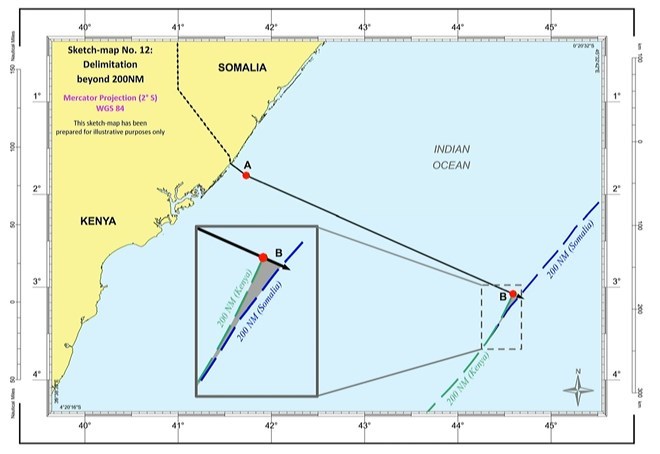

The 100,000-square-kilometer offshore area has been the center maritime territorial dispute between the two neighboring countries since 2014. The dispute stems from a disagreement over boundary demarcation over the triangular patch of ocean, which Kenya claims was in 1979 created by a boundary line running east in a straight line parallel to the Equator from the country’s coastal border with Somalia. However, Somalia insists the boundary of the disputed area should be demarcated by a line running southeast of its land border.

In its ruling, the ICJ handed a sizeable portion of the disputed offshore Indian Ocean area, which contains two significant fishing zones, to Somalia, despite acceding to Kenya’s request to shift part of the shared maritime boundary to the north.

It is unclear whether Kenya, which withdrew from the case and vowed to ignore the final verdict, will comply with the ICJ ruling. It claimed in a submission to the court that there “is an existing maritime boundary that was established in 1979.”

“The boundary as established has been respected by both countries until 2014, when Somalia attempted to repudiate the agreement by dragging Kenya to the International Court of Justice seeking to appropriate Kenya’s maritime space,” it said. “The government and people of Kenya feel betrayed that Somalia had brought the case before the ICJ after repudiating a maritime boundary that it had consented to for over 35 years.”

Kenyan fishing associations and the leadership of the Kenya's Lamu County government issued statements expressing their concern over the ICJ ruling.

“If Kenya and, in the smaller context, Lamu loses the maritime waters that it holds to Somalia, we could be losing as much as KES 7.5 billion (EUR 57.6 million USD 67.1 million) worth of income annually,” Lamu Fisheries Chief Officer Simon Komu told the state-sponsored Kenya News Agency.

Lamu Fishermen Association Chairman Somo Bin Somo said losing the fishing grounds, especially the Kiunga fishing area, will force many fishers to "leave fishing altogether."

"We might end up being subjected to the cruelties that our brothers in Migingo [on Lake Victoria] are enduring at the hand of Uganda because of a maritime water dispute," Somo said. “Not only is 80 percent of Lamu’s economy dependent on the blue economy sector, but 65 percent of Lamu’s rich fishing grounds are based in the disputed maritime waters of Kiunga area."

The ICJ ruling adds to the woes facing Kenya’s fishing sector, particularly in Lamu County, which has been impacted by a decline in the country's total fish landings. The Lamu region recorded a 7.2 percent drop in landings in 2020, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

The disputed maritime area, also thought to be rich in oil and gas, has previously been linked to incidents of human trafficking, smuggling of contraband goods, and illicit drug trade, which led to a ban in 2019 on night fishing by the Kenyan government. The ban was later lifted.

Many fishers in Lamu can already no longer access some fishing grounds after they were displaced to pave way for the construction of a USD 5 billion (EUR 4.3 billion) Lamu Port Project under the Lamu Port South-Sudan Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor Program.

Although Kenya's High Court ordered the government to pay a combined KES 1.76 billion (EUR 13.5 million, USD 15.7 million) to around 4,600 fishermen impacted by the project, the country's government has not yet agreed to disburse the funds.