By Tom Collins

Saturday April 9, 2022

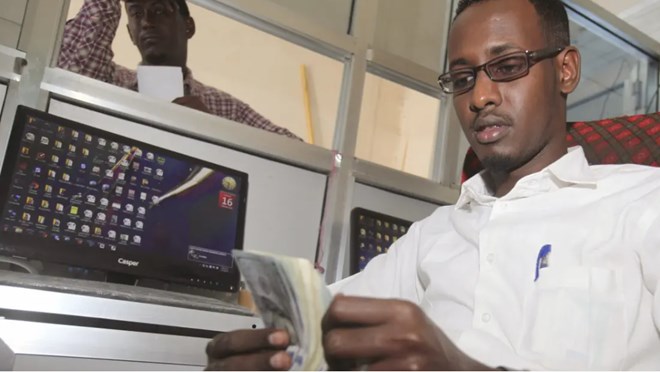

Innovations from Somalia range from the early adoption of the Hawala system to global money transfer companies of Somali origin including World Remit and Dahabshill.

Somalia’s money transfer market is one of the most developed

in the world, characterized by a large diaspora sending billions of dollars

home in remittances each year and a local population that prefers mobile money

to cash.

Latest data from the World Bank in 2017 suggests that 73% of

the population above the age of 16 use mobile money services—making Somalia one

of the most dynamic markets in Africa and worldwide.

Despite only being introduced 10 years ago, over two thirds

of all payments in Somalia now rely on mobile money platforms.

Although Hormuud, Somalia’s leading mobile money provider,

only received GSMA Mobile Money Certification in March, a global standard of

telecoms excellence, the country has changed the face of money transfers

worldwide for decades.

newsinisdeThe major factors behind the country’s innovation in money

transfers are a tough operating environment, a weak banking system, lack of

policy implementation, and deep distrust of government and the local currency.

“It’s the culture in our community, we are risk takers. Due

to the challenges, we have had to explore new ideas.”

Innovations range from the early adoption of the Hawala

system to the global rise of money transfer companies of Somali origin

including World Remit and Dahabshill.

“Anyone who has a mobile has mobile money services,” says

Abdullahi Rage, a Mogadishu-based research analyst at the African Center for

Strategic Progress, a US think tank.

“The problem in Somalia is that we have a lack of data—it’s

hard to get an exact number. But I would say more than nine out of 10 people

use mobile money in Somalia.”

Somalia’s challenging

market sets stage for innovation

Somalia has long been a challenging market with deep divides

in government that often spill over into armed conflict and parts of the

country under the control of terrorist group al-Shabaab. But these problems

have created the perfect hotbed for innovative solutions, especially with

regards to financial technology.

“It’s the culture in our community, we are risk takers. Due

to the challenges, we have had to explore new ideas,” says Ahmed Mohamed

Yuusuf, CEO and chairman of Hormuud, one of Somalia’s biggest telcos with 4.5

million subscribers.

The first innovation was the early adoption of the hawala

money transfer system, which originated in 8th century India and spread to the

Horn of Africa and the Middle East. The service allows users to send and

receive money in different countries through an informal network of brokers,

without any funds crossing borders.

This method of money transfer was popular in Somalia before

mobile money and continues to this day, with most brokers moving into the

formal telecoms industry. Yuusuf says that up to 45% of the hawala agents in

Somalia, who mostly process payments from the US and UK, use Hormuud’s EVC Plus

mobile money to do business.

The chairman of the group says it was the high costs,

inefficiencies, and structural barriers associated with Somalia’s legacy

banking system that previously drove people to the hawala network and the same

is true of mobile money.

A market like nowhere

else

Somalia has an extremely competitive mobile money market

with lots of small-sized players rather than a few large companies like other

markets in Africa. In comparison to neighboring markets like Kenya, which is

home to Safaricom’s M-Pesa, one of Africa’s most well-known mobile money

services, cash is transferred in dollars and most telecoms companies do not

charge a fee for transfers.

When Hormuud launched EVC Plus in 2011, Yusuuf says they

made it a free service to encourage Somalis to adopt the financial technology.

Instead of using EVC Plus to generate revenue, it is used to onboard clients to

other services such as data and voice.

The remittance version of EVC Plus, however, is a charged

service. Yusuuf says that it is often used by humanitarian organizations to

help deliver aid to Somalia. More than $200 million has been sent to Somalia in

the last few months on the platform as the country suffers its worst drought in

decades, where more than 4 million people are at risk of starvation.

Indeed, Somali has a dynamic remittances sector with more

than 2 million citizens living outside the eastAfrican country. The UN

Development Programme estimates that $1.6 billion is sent back to Somalia each

year – almost a third of the country’s GDP which was $5.42 billion in 2021.

One of the most well-known companies to emerge from Somalia

is World Remit, a money transfer company that was founded in 2009 by a

Somaliland entrepreneur who was frustrated by the lack of remittance options

when he arrived in the UK as a refugee.

“We don’t have a national ID in place and therefore

identifying customers was a bit of a challenge.”

Somalis also transfer money between mobile accounts in

dollars as the Somali shilling is very unstable and the IMF says that around

98% of the local currency in circulation is fake. The lack of faith in physical

money is another key reason why mobile money has been so successful in Somalia,

leading to a situation where it has almost completely replaced the Somali

shilling in some parts of the country.

Research shows that Somalia processes some 155 million

transactions a month in a population of only around 17 million people. Most people

keep their money in a digital wallet as opposed to a physical bank.

Lack of oversight a

concern

One of the main problems in the domestic market, however, is

the lack of regulation for mobile money. Fragile institutions and ongoing

political risk have delayed robust legislation that can regulate the mobile

money industry to ensure it benefits consumers and the country.

This has sparked concerns that mobile money is being used

for illicit finance and to support al-Shabaab.

“It’s a challenge to control the flow of money in and out of

the country,” says analyst Rage. “But private companies are doing their best to

at least have checks and balances”.

A good example is Hormuud which received Somalia’s first

GSMA Mobile Money certification in March. The certification from the world’s

leading industry organization is a milestone for Somalia’s telecoms sector and

puts Hormuud among the top mobile money providers in Africa for safety and

security.

The CEO tells Quartz that the company had to meet 350

different criteria and that know your customer (KYC) requirements were the

hardest to meet.

“We don’t have a national ID in place and therefore

identifying customers was a bit of a challenge,” he says. “But then there are

other mechanisms in place, for example records provided by local authorities”.

One of the key challenges was making sure that the rigorous

standards required by GSMA did not discourage financial inclusion for Somalis

that do not have access to formal identification. The solution was to lower the

maximum amount unidentified users could hold on a digital wallet to $300, which

reduced the likelihood that it would be used for illicit finance.

Despite the lack of a strong regulatory body, Yuusuf says

that there have been some recent improvements. Somalia’s central bank awarded

Hormuud with Somalia’s first mobile money license in 2017—a sign to investors

that the local market is maturing. It also introduced a central payments system

in August which allows digital payments to be made between Somalia’s banks,

making payments easier for people across the country.

Moving to digital in

Somalia

The biggest challenge for Somalia’s telecoms industry is the

transition away from analog phones to smartphones. The World Bank found that

49% of the population owned a mobile phone in 2019 but most of the phones were

feature phones that use USSD technology to access mobile money.

“It’s not digital, it’s not internet based,” says Rage.

“Mobile penetration in the country is high compared to low internet

penetration”.

This poses a challenge for telecoms companies that are keen

to introduce data as an income generating stream. The CEO of Hormuud says that

it is currently investing heavily in fiber optics to ensure that “every family

has access to the internet”.

“Voice is dying out. Things like WhatsApp and other apps are

coming in, so our focus at the moment is on extending and monetizing data

services,” he says.

Tom Collins is a financial journalist, editor and consultant covering markets and

businesses in Africa.