Wednesday August 3, 2022

By Bruce Hoffman

Ayman al-Zawahiri leaves behind a robust network of strategically aligned but tactically independent al-Qaeda affiliates operating in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

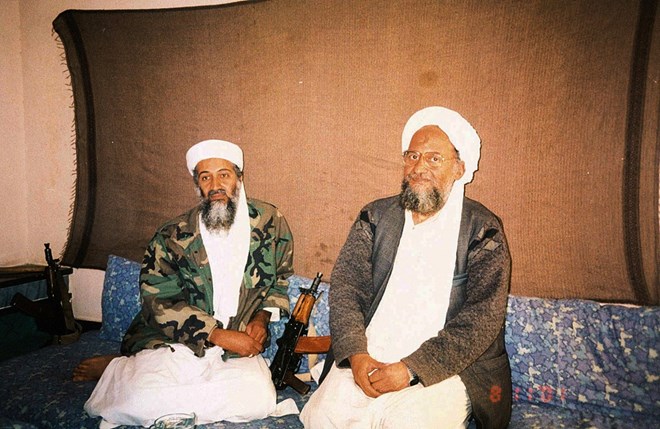

FILE PHOTO: Osama bin Laden sits with his adviser Ayman al-Zawahiri, an Egyptian linked to the al Qaeda network, during an interview with Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir (not pictured) in an image supplied by Dawn newspaper November 10, 2001. Hamid Mir/Editor/Ausaf Newspaper for Daily Dawn/Handout via REUTERS/ THIS IMAGE HAS BEEN SUPPLIED BY A THIRD PARTY./File Photo

President Joe Biden revealed that a U.S. drone strike killed al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri over the weekend. How much of a role did Zawahiri play in the movement?

Zawahiri was critical to al-Qaeda’s survival in the decade since the 2011 killing of its previous leader, Osama bin Laden. He held the movement together through his force of personality and strategic vision, which was to allow the various al-Qaeda franchises to pursue their local and regional agendas and have complete tactical independence. It has been successful. Both al-Shabaab and Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) have a robust presence in East Africa and the Sahel, respectively; al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula is still fighting in Yemen; Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent has spread to Bangladesh, India, the Maldives, Myanmar, and Pakistan; and Hurras al-Din remains Al-Qaeda’s stalking horse in the Levant. None of this would have been possible without Zawahiri. Even though the al-Qaeda affiliates have had enormous independence, they have also adhered to the group’s ideology and conformed to Zawahiri’s strategy. That will continue.

What’s next for al-Qaeda?

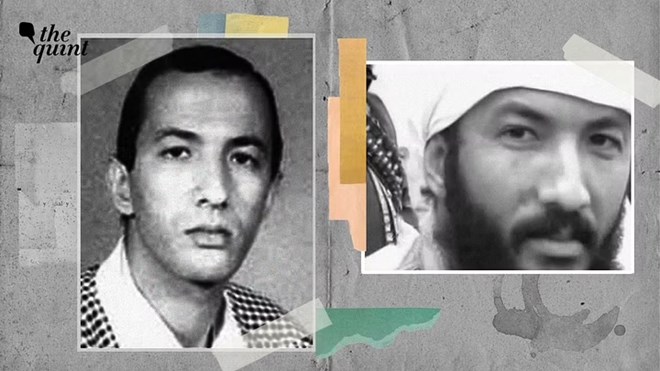

Al-Qaeda has a succession plan, and Saif al-Adel, a long-standing senior al-Qaeda commander, is the most likely candidate to succeed Zawahiri. A former officer in an Egyptian Army special operations unit, Adel played a critical role in the 1998 bombing of the American embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; orchestrated al-Qaeda’s failed terrorist campaign in Saudi Arabia in 2003; tutored and mentored Hamza bin Laden, Osama’s son and reputed heir as al-Qaeda emir; and, in recent years, oversaw al-Qaeda’s operations in Syria.

Adel should be effective in holding the al-Qaeda universe together. After all, in a few days, al-Qaeda will celebrate its thirty-fourth anniversary. A terrorist group doesn’t survive three-plus decades being dependent on one leader only. The State Department’s list of foreign terrorist groups now contains four times as many groups sharing al-Qaeda’s ideology than it did on 9/11. So, one way or another, the war bin Laden declared more than quarter a century ago will continue at some level.

Seif Al Adel/ SOURCE: FBI

Zawahiri was living in Kabul, Afghanistan, at the time of his death. What is the significance of that?

It is highly significant that he was residing in Kabul, presumably with the Taliban’s full knowledge. This demolishes the Taliban’s claims that they have severed ties with al-Qaeda, but rather confirms that the group is nothing other than an intimate partner and ally. Zawahiri wasn’t living in a cave near some remote village on the border with Pakistan, but in a mansion in a part of Kabul where Western diplomats lived. He was clearly a Taliban intimate and treated with great deference and respect. This will undermine the Taliban’s efforts to negotiate with the United States to unfreeze the $9 billion in assets that Washington is holding.

How much of a threat does al-Qaeda pose compared to other Islamist groups?

Al-Qaeda under Zawahiri was deliberately playing a long game, content to quietly rebuild and regroup while the world focused on defeating the self-declared Islamic State and destroying its caliphate. Zawahiri’s strategy was two-fold: one, to let the Islamic State absorb all the attention of the United States and its allies while al-Qaeda marshaled its strength to continue its three-decade-plus struggle; and two, to portray al-Qaeda as moderate extremists—a more reliable and less ephemeral force than the impetuous and hyper-violent Islamic State. Zawahiri’s quietist strategy was validated by the patience and perseverance that returned the Taliban to power. So, while the core al-Qaeda has been less active than other Islamist rivals or even its own franchises, but that doesn’t mean that it has eschewed terrorism or given up its struggle.

What does this strike say about the Biden administration’s counterterrorism approach?

Zawahiri stood on his balcony daily in broad daylight. The U.S. intelligence community had tracked the movement of his wife, daughters, and grandkids to the mansion in a tony part of Kabul. It then identified Zawahiri coming to join them. I am not implying that any of this intelligence work or the strike itself was easy, only that Zawahiri and his family were doing these things all in plain sight—that’s how secure he and the Taliban felt.

A television screen shows Ayman al-Zawahiri in 2001. Maher Attar/Getty Images

So, yes, Zawahiri’s death is tremendous news, but it is not yet proof positive of the effectiveness of Biden’s “over-the-horizon” counterterrorism strategy. It would be an intelligence success of a different magnitude if current U.S. counterterrorism efforts in Afghanistan also effectively disrupted the planning and formulation of actual terrorist attacks. But the strike on Zawahiri does invalidate the claims of pundits who last week—on the CIA’s seventy-fifth anniversary—said it was a mistake for the CIA to focus so much on counterterrorism and high-value targeting after 9/11 and not enough on bread-and-butter intelligence collection. The CIA’s pivotal role in bin Laden’s Zawahiri’s deaths shows the strengths and peerless capabilities of the CIA and the broader intelligence community.