Friday June 17, 2022

By: Zanta Nkumane

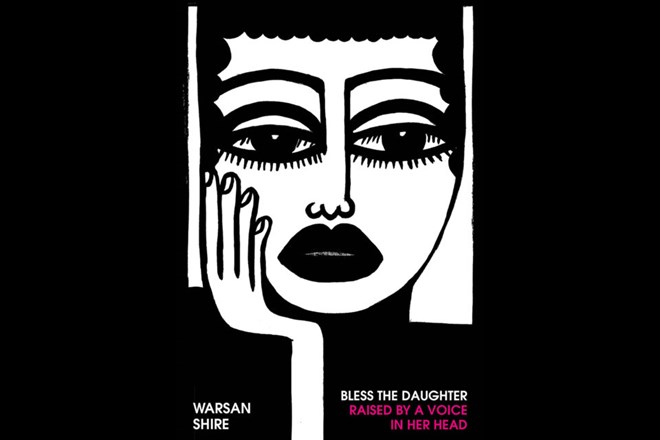

Illustrator: Anastasya Eliseeva

The British Somali poet draws readers into migrant life in Bless the Daughter, a collection that reflects her attempts to create a sturdy sense of home and belonging.

A poet’s ability to conjure sprawling yet intimate worlds in few words is an enviable skill. One such poet who hems you into their world is Warsan Shire, demanding attention from her first line to her last.

Bless the Daughter Raised By the Voice In Her Head, Shire’s first full-length collection of poems, thrusts readers back into a story she began about 10 years ago with her chapbook, Teaching My Mother How To Give Birth.

“It was always an extension of my chapbook. My chapbook was almost like this peek into the world I grew up in – secret, violent, but also glorious lives that are usually invisibilised, overlooked or underestimated,” she says over a video call.

In the years since it was published, the poet has made some staggering achievements. She was selected as the first Young Poet Laureate for London, elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and collaborated with Beyonce on the Lemonade and Black Is King music films – her words are interspersed between the songs and contribute to the narrative backbone of the films.

Yet despite a glowing career, Shire did not feel any pressure when putting this debut collection together. She knows that the folly of rushing can marshal writers into work they might not be proud of. “I’m just not somebody who is going to be rushed. I don’t really see life in that rat race kind of way. Nothing that is yours can be taken from you,” she says.

A sense of belonging

An ample portion of Bless the Daughter, like Shire’s previous work, widens insight into the interior world and lives of immigrants and refugees.

A migrant’s life can feel scattered across the many places they’ve lived and bruised by the constant feeling of being unwelcome. Shire crochets these scattered parts together through her poetry in an attempt to create a sturdy sense of belonging and home.

“This homelessness I felt is exacerbated by growing up in London and losing our home. Then experiencing homelessness in London. I think I always felt this uprootedness. Up until now, I have a lot of anxiety around housing instability,” she says.

Shire was born in Kenya to Somali parents. At the age of one, they migrated to the United Kingdom. She currently lives in Los Angeles, California, in the United States. “Even just last night, I had a stress dream where I was told that in one hour we had to pack everything in the house. I had to do it by myself while my mom was in the corner, berating me. I have these dreams constantly about having to quickly rush and pack everything up, and get out of the country.”

Shire acknowledges that this enduring anxiety is a ramification of her parents having to do that, and she was with them. Losing their home forced the family to stay with relatives, which inculcated in her a weighted and lingering sense of always being the guest. Pinning down concepts of home in poems and writing in general countered this belief, she says.

All amalgamations

As we speak, Shire emphasises a particular tension in the book between the awareness of not being welcome and simultaneously feeling at home. “It’s a strange feeling. You’re never going to be truly from here even though all your memories are going to be based there, all your ideas of nostalgia and all your first times are going to be in that country, but you’re never going to be from there,” she says. But even among this maelstrom of uprootedness is the revelation that, in some way, she has found a freedom in not belonging.

“Straddling countries, cultures and languages gives you this ability to kind of belong everywhere, not necessarily nowhere. But that home, you can make it,” she says. “I don’t have that deep connection with one place – it’s all of them, all the time.”

This compounding of cultures and languages is apparent throughout the book and creates a textured and informative narrative, mottled with muslim traditions, Arabic sentences, news headlines and pop culture references. This device is Shire’s way of showing that we are all amalgamations of different cultures, influences and experiences.

One of the people who appears in many of the poems is Shire’s mother. It’s clear that their mother-daughter relationship is tumultuous in the way she conveys both a gaping frustration with and fervent adoration for her mother in poems such as Bless the Real Housewife and Hooyo Full of Grace.

Shire explores the bond between mother and child by querying what happens when that bond isn’t strong. “The mother and child rejecting one another is so unnatural it could create a monster. If it’s fractured in some way, you feel what they call the mother wound. That’s my biography, my memoir – that’s my life basically.”

‘The consequences of parents’

In Bless the Daughter, there is an acknowledgement that she considers her mother beautiful and fascinating, but her mother’s struggles with being maternal affected her deeply. Even through this wounding, she remains empathetic, understanding her mother’s childhood.

“But with my mama, I knew her inability to really be nurturing was completely linked to her trauma and me giving language to that for her and for myself and her mother and her mother before her is freeing it up, so that my children and their children do not have to struggle with the consequences of parents,” she says.

Since becoming a mother herself, she has an extra level of empathy for her mother. And because Shire wanted to be a mother, she accepts the possibility that maybe, in an ideal world, her mother would have chosen to be child-free. “In Islam they say after God, it’s your mama. I’m constantly thinking about God, I’m constantly thinking about my mama, I’m constantly thinking about my children. It’s this thing of what comes before you, what comes after you.” In this way, the book becomes a memorial of the past, a clear-eyed look at the present and an instruction for the future.

As in the title, Shire uses the word “bless’” across the book. It appears in many of the titles and verses. Sometimes it sits alongside macabre descriptions and this feels intentional, too. “This book is a book of blessings for the blessless or unblessed or those that are usually forgotten out of people’s prayers,” she says.

Her most special poem is Victoria In Illiyin. The poem is about Victoria Climbié, an Ivorian child raised by her extended family. Her great-aunt and great-aunt’s boyfriend tortured and murdered her in a London flat. She died aged eight with 128 injuries to her body. “That poem means that every time somebody reads it or I read it out, it’s all of us constantly blessing her. In a way, she is a saint and we all pray for her.” Shire wields the transformative power of poetry throughout the book to “turn the grotesque, inhumane things we do to one another. We can still find a sliver of hope or beauty.”

Bless the Daughter Raised By the Voice In Her Head may be tiny in size but it delivers emotional carnage, verse after verse. It’s work that is moulting, inventive and that feels like “notes on survival”. In writing it, Shire not only cements herself as an archivist for her community but also establishes herself as a translator of feelings, experiences and thoughts from a clearly defined particularity into the universal.