Wednesday June 29, 2022

By Catherine Garcia

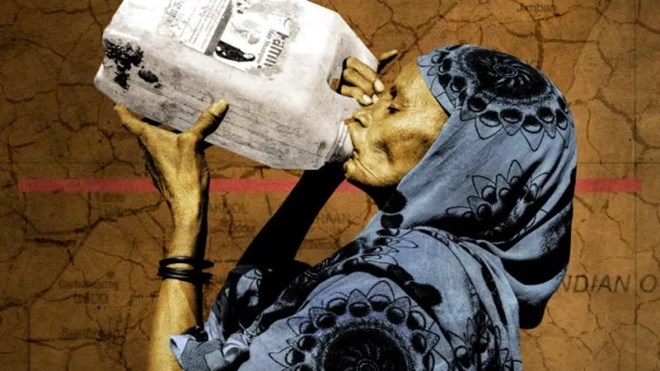

A woman drinking water. Illustrated | Getty Images, iStock, Library of Congress

A woman drinking water. Illustrated | Getty Images, iStock, Library of Congress

After four dry rainy seasons, Somalia is experiencing its worst drought in 40 years — that, coupled with an increase in food prices, is causing humanitarian officials to warn that many people may soon face famine unless there's an increase in funding and humanitarian aid. Here's everything you need to know:

What's causing the drought in Somalia?

Scientists are not entirely sure if this drought is directly connected to climate change, The New York Times reports, primarily because due to years of conflict in the area, there isn't enough rainfall data to look at. Still, the Times' Raymond Zhong says, scientists do expect the "frequency, duration, and intensity of droughts in the region to increase if global warming reaches higher levels. The warmer atmosphere would mean the land gets drier and stays drier. There would be bigger swings in rainfall. So even if this drought wasn't made more likely or more intense by global warming, future ones might easily be."

Humanitarian agencies, however, disagree. Jan Egeland, secretary-general of the Norwegian Refugee Council, told Democracy Now! this is "a creeping, devastating drought, which is coming after four failed rainy seasons. So it's climate change. It's the climate change that we in the industrialized world caused. And who is dying from this? The children of Somalia, from a people who did nothing to cause climate change." Mohamud Mohamed, Save the Children's country director in Somalia, said in February that previous events show "the ultimate culprit is climate change." Somalia has "always had droughts," he explained, and "Somalis have always known how to deal with them — they struggle, they lose livestock, they count their losses, and then they bounce back. But now, the gaps between droughts are shrinking. It's a killer cycle and it's robbing Somali children of their future."

How many people are facing hunger in Somalia?

The drought — which has already displaced 560,000 people — is leading to widespread hunger in Somalia, and in mid-June, it was estimated that nearly half of the 16 million people believed to be living in the country do not have enough food to eat. In November 2021, a Save the Children humanitarian assessment found that almost 700,000 camels, goats, sheep, and cattle had died from drought-related causes in just two months — this has hurt families in two ways, as they lost food and a source of income.

On top of that, Somalia imports more than half of its food, and almost all of its wheat comes from Ukraine and Russia. That supply chain has been disrupted since Russia invaded Ukraine in February, and because of the war, the cost of food has steadily increased in Somalia in the last several months. UNICEF says due to the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine making ingredients and packaging more expensive, it's projected that the price of a peanut-based paste given to children to help with malnutrition will jump up 16 percent.

How are the drought and food scarcity affecting children?

The situation for children is dire, with kids dying every day from malnutrition. Adam Abdelmoula, the U.N. humanitarian coordinator for Somalia, told Democracy Now! last week that 1.5 million children under the age of 5 are already malnourished, "and we expect that 366,000 of them may not survive through the end of September of this year."

Claire Sanford, deputy humanitarian director for Save the Children, told The Guardian last week that she has met multiple mothers in Somalia who have had to bury more than one child this year due to malnutrition. "I can honestly say in my 23 years of responding to humanitarian crisis, this is by far the worst I've seen, particularly in terms of the level of impact on children," Sanford said. "The starvation that my colleagues and I witnessed in Somalia has escalated even faster than we feared."

The Times spoke with one woman, Hirsiyo Mohamed, who saw her crops fail and goats die because of the drought. A mother of eight, she spent four days walking from her home in southwestern Somalia to an aid camp in the town of Doolow. Before she arrived, her 3-year-old son, Adan, died, after begging her for food and water. "We buried him and kept walking," Mohamed told the Times. Once at the camp, her 8-year-old daughter, Habiba, already suffering from malnutrition, came down with whooping cough and died. "This drought has finished us," Mohamed said.

Is famine in Somalia inevitable?

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification defines famine as "the absolute inaccessibility of food to an entire population or sub-group of a population, potentially causing death in the short term." Abdelmoula said there are eight districts in Somalia that are already experiencing famine, at a "catastrophic" level, and he warns "that number is bound to increase, unless — unless — we are able to scale up our response plan in a very, very major way." This is especially critical as the next rainy season is also expected to produce below-average precipitation.

What can be done to help Somalia?

The country needs money, urgently. Michael Dunford, the World Food Program's regional director for east Africa, made an appeal to G7 leaders last week, saying there must be a "massive scaling-up" of aid in order to avoid total catastrophe. Immediately, Somalis need food and water, and money must also be set aside for other measures, like protecting livestock and reforestation. Funding has been slowly trickling in; the U.N. says aid donors have pledged just 18 percent of the $1.46 billion it needs for Somalia.

The World Bank recently approved $143 million in International Development Assistance financing, which will deliver cash to vulnerable households. Individuals can also donate to organizations like Save the Children and the Somalia Humanitarian Fund.

Are there other countries in Africa facing this drought?

Yes. While the situation is most severe in Somalia, the drought is also affecting millions of people in Kenya and Ethiopia. The World Food Program says in Ethiopia, "hunger is tightening its grip on more than 20 million Ethiopians who are facing conflict in the north, drought in the south, and dwindling food and nutrition support," and it is running out of money to keep up its operations helping "acutely malnourished" women and children.