The New Humanitarian

Abdalle Ahmed Mumin

Freelance journalist in Mogadishu

Friday May 13, 2022

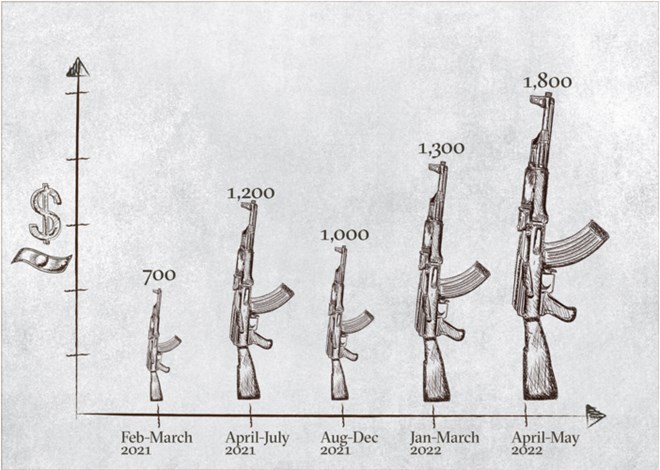

The price of an AK-47, the standard weapon of Somali

militias, has soared on gun markets ahead of a fraught ballot this weekend,

when lawmakers will select the country’s next president.

Parliamentarians from Somalia’s lower and upper houses will

decide on 15 May from a list of 39 candidates that includes two former

presidents, an ex-prime minister, as well as the second term-seeking incumbent,

Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, known as “Farmajo”.

Tensions are high in the run-up to the vote, especially in

Mogadishu; the capital, and the stronghold of the powerful Hawiye clan, who are

opposed to Farmajo.

Armed clashes broke out in April 2021 when politicians

resisted Farmajo’s attempt to extend his first term by two years. The president

said it was to allow long-delayed elections to be held, but his critics

interpreted it as a “power grab”.

The fear is that a disputed vote on Sunday could trigger

even worse violence. As a result, the price of a standard AK-47 has more than

doubled since last year – up by nearly 40 percent in just the last few months,

according to research by The New Humanitarian among gun traders.

Infographic: Average AK-47 prices in Mogadishu. Source: Research by The New Humanitarian in local gun markets.

Demand is also high for belt-fed PKM machine guns and RPGs,

the equipment needed for full-scale fighting, said Mogadishu-based gun merchant

Ali Nur.

Prices dipped towards the end of last year (see the table

above), after Farmajo agreed to abandon his term extension plan and allow Prime

Minister Mohamed Hussein Roble to push through parliamentary elections. But the

fall was short-lived as political distrust ratcheted up once more.

“Politicians want to protect themselves, and so do their

clans,” Nur told The New Humanitarian. “In Somalia, your only protection is the

number of weapons you have.”

Political arithmetic

Amina Mo’alim, who works as a cleaner in a downtown hotel,

is worried about what could happen in the coming days. She had to flee the 2021

fighting, along with an estimated 100,000 others, many of them the urban poor –

survivors of frequent droughts, and a long-running jihadist conflict in the

countryside.

“None of the presidential candidates have publicly

acknowledged they will concede if they lose,” she told The New Humanitarian.

Like many other Somalis, she has stayed at home foregoing her pay this week as

a precaution, and is prepared to do so again next week.

Abdirahman Hassan, a government worker, shares those

concerns. “Every day, I hear about new weapons purchased and tested in Hodan

district [the main gun market],” he told The New Humanitarian. “People are

saying, ‘if the incumbent president is defeated and does not concede, it will

lead to fighting’.”

Clan-based arithmetic – on which Somali politics is based –

suggests Farmajo might struggle to find the votes needed to be re-elected when

the lawmakers meet on Sunday.

The five regional states that have sent a slate of

parliamentarians to Mogadishu. Two – Puntland and Jubbaland – are expected to

back the opposition; Galmadug and Hirshabelle are a toss-up; while only one,

South West, has declared for Farmajo.

Clan power

Since the collapse of Somalia’s last central government in

1991, clans have been central to political power.

The make-up of Somalia’s 275-seat lower house is based on a

so-called “4.5” formula: Each of the four “major” clans – the Hawiye, Dir,

Darod, and Rahanweyn – has 61 seats; minority groups, known as “point five”,

share the remaining 31 seats. State representatives sit in the 54-seat upper

house.

Farmajo, a Darod, came to power in 2017 and was initially

hailed by some as a reformer. He had broken the political dominance of the majority

Hawiye and promised the next election would be under a “one-person, one-vote”

system, rather than the clan-based, indirect ballots of the past – a pledge he

did not deliver on.

Since the clashes last April, Somalia’s fragile security

forces have also splintered along clan lines – despite years of Western donor

funding. Although the bulk of the army is believed to side with the opposition,

Farmajo has the loyalty of new special forces units trained and equipped by

Turkey and Eritrea.

Mohamed Adan, a police captain who monitors the illegal

weapons markets, believes the perceived politicisation of the security forces

is one reason people have turned to their clans for protection.

“In the past five years, the government has [used the

security forces] to silence and attack dissidents, including opposition

politicians,” he told The New Humanitarian. “This has led to the resurgence of

clan militias.”

Al-Shabab as well

Much of what’s available for sale on the gun markets in

Hodan is from stocks diverted illegally by members of the armed forces – a

further example of the hurdles to security sector reform that has bedevilled

attempts to build a professional national army.

Any collapse into serious fighting will only benefit the jihadist group

al-Shabab. It has battled Somali governments for two decades, viewing

successive administrations as corrupt and dependent on Western governments for

their survival.

The al-Qaeda linked insurgents, who hold much of the

countryside, have launched a flurry of urban bombings throughout the election

period, which began with parliamentary polls in November.

The lawmakers meeting on Sunday will do so in an airport and

diplomatic zone protected by African Union forces, deployed for the past 15

years to prop up governments in Mogadishu.

If political violence does break out, the “little security

gains will be reversed and will strengthen al-Shabab to retake urban towns that

had been liberated years ago”, Dahir Hassan, a security analyst and former

Somali military officer, told The New Humanitarian. “The group [has already

gained] more power because the government has shifted its focus from security

to politics.”

Edited by Obi Anyadike