Saturday May 14, 2022

Somalia will hold a long-awaited presidential election on

Sunday, ending months of delays, with the new leader set to confront huge

challenges including a grinding Islamist insurgency and a punishing drought

that has sparked famine fears.

The troubled Horn of Africa nation has been grappling with a

political crisis since February 2021, when President Mohamed Abdullahi

Mohamed's term ended without a new vote.

The 39 candidates include the incumbent, better known as

Farmajo, as well as past presidents Sharif Sheikh Ahmed and Hassan Sheikh

Mohamud and former prime minister Hassan Ali Kheyre.

Puntland state president Said Abdullahi Dani and former

foreign minister Fawzia Yusuf Adan -- the lone female contender -- are also

among the record number of candidates vying for the top job.

All have vowed to tackle Somalia's myriad problems and bring

relief to citizens weary of violence by Al-Shabaab jihadists, surging inflation

and a worsening drought.

The vote is expected to draw a line under a political crisis

that has lasted well over a year, after Farmajo attempted to extend his rule by

decree, triggering violent street battles as rival factions clashed in the

capital Mogadishu.

Following international pressure, he appointed Prime

Minister Mohamed Hussein Roble to seek consensus on a way forward, but progress

has been painfully sluggish, dogged by claims of irregularities and political

interference.

The growing rift between the two men has not helped matters,

while the central government has also been embroiled in disputes with certain

states, further slowing down the voting process.

- 'Reset button' -

"This electoral process that has been so protracted

offers a reset button," said Samira Gaid, executive director of the Hiraal

Institute, a Mogadishu-based security think tank.

"The country is very polarised at the moment and you

expect that whoever comes in will work towards reuniting the country," she

told AFP.

Somalia has not held a one-person, one-vote election in 50

years.

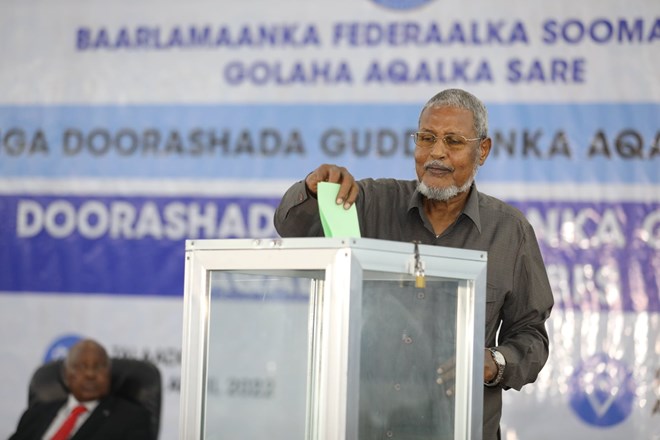

Polls follow a complex indirect model, whereby state

legislatures and clan delegates pick lawmakers for the national parliament, who

in turn choose the president.

The winning candidate must secure the backing of two-thirds

of parliament, which means a minimum of 184 votes.

With 39 people up for the presidency, the complicated

process is expected to require multiple rounds of voting and stretch late into

the night.

"In terms of predicting the outcome, Somalia politics

is notoriously difficult to predict, especially because it is an indirect, sort

of closed system with MPs voting for the president," said Omar Mahmood, an

analyst at the International Crisis Group (ICG) think tank.

"At the end of the day, I think it's... predominantly

about alliances and relationships rather than concrete ideas," he told

AFP.

- Challenges ahead -

Somalia's global partners, which include the United States,

the African Union and the United Nations among others, this week urged the

country's leaders "to conclude this final stage of the electoral process

swiftly, peacefully and credibly so that attention can turn to domestic and

state-building priorities".

The international community has long warned Somalia's

government that political infighting and election delays have allowed the

Al-Qaeda-linked Al-Shabaab to exploit the situation and carry out more frequent

and large-scale attacks.

Twin suicide bombings in March killed 48 people in central

Somalia, including two local lawmakers.

Last week, an attack on an African Union base killed 10

Burundian peacekeepers, according to Burundi's army. It was the deadliest raid

on AU forces in the country since 2015.

While the insurgency has dragged on for over a decade, the

economy has been on life support, with over 70 percent of Somalia's population

living on less than $1.90 a day.

The country's financial fortunes are hugely dependent on the

successful completion of Sunday's election.

A three-year $400-million (380-million-euro) aid package

from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is set to automatically expire by

mid-May if a new administration is not in place by then.

The government has asked for a three-month extension until

August 17, according to the IMF, which has not yet responded to the request.

Graft remains a persistent problem for Somalia, which sits

near the bottom of Transparency International's world corruption index, ranking

178 out of 180 nations.

The new president will also have to tackle the country's

crippling drought, which threatens to drive millions into famine, with young

children facing the greatest risk.

UN agencies have warned of a humanitarian catastrophe unless

early action is taken, with emergency workers fearing a repeat of the devastating

2011 famine, which killed 260,000 people -- half of them children under the age

of six.

Additional sources • AFP