Tuesday February 7, 2023

By PABLO GUIMÓN

A mother holds her son in her arms at Trócaire Hospital, which treats infant malnutrition, in Dolow, Somalia. Photo: ÁLVARO GARCÍA

Dolow (Somalia) - In the camps for displaced people in Dolow, southern Somalia, there are things that look like children’s games, but in reality, they are signs of the unfolding humanitarian catastrophe in the country. Here children control cylindrical balls instead of soccer balls, yellow drums that they roll on the ground with their bare feet. They fill them in the crowded points where humanitarian organizations have installed taps from which flows the liquid that the sky has denied them for so long. They advance with short passes to their huts, made of twisted dry sticks and covered with tarpaulins, which form a vast colorful stain in this flat and arid land, one that is expanding on a daily basis with a relentless trickle of families fleeing a deadly combination of Islamist extremism and the worst drought the Horn of Africa has seen in 40 years.

Here, balls are not balls and swings are not swings. The closest thing to one can be found at the entrance of the precarious Trócaire hospital: a black plastic bucket hanging from four ropes tied to a scale attached to a wooden frame. The swaying of the swing elicits no reaction from its occupant, four-year-old Rahma. Lack of interest in play is one of the telltale signs of a malnourished child. The measuring tape attached to her arm, an instrument used by health workers to detect malnutrition in children, confirms what her half-drooping eyelids and disarming expressionlessness had already conveyed. The tape stretches across less than 11 centimeters of her bicep. Red: severe malnutrition.

Now Rahma is lying in one of the beds inside the hospital, which has had to be expanded by means of a tent to keep up with demand. Next to her, her mother, Fatima Hussein, 30, explains that Rahma “has never been a smiling child. She’s always been sick, she doesn’t play with her siblings, she’s always been like that,” she says in a whisper lost in the crying of babies as she gently chases flies away from Rahma’s face with one end of her hijab. The drought ruined the small parcel of land the family cultivated and killed what little livestock they had. After her second son died, Fatima realized they had to flee. Three days in a cart pulled by two starving donkeys loaded with their meager belongings, past jihadist checkpoints, until they reached the Ladam refugee camp in Dolow. Along the way she lost a third son. Fatima is reluctant for Rahma, the second-youngest of her six remaining children, to meet the same fate. “The situation is still very hard. It hasn’t rained in the two years we’ve been here. But I will do my best to get her healthy. And when she is healthy, she will be happy for sure.”

The rains that won’t come

Somalia has two rainy seasons per year and, in a society where subsistence farming reigns supreme, thousands of households are pushed to the limit if the waters do not come. The past five rainy seasons have failed to materialize, and no one is particularly optimistic the next one will be any different. At least 3.8 million Somalis have abandoned their homes and many are crowded into displacement camps like the five that have sprouted up around Dolow. The UN estimates that by this summer, there will be 1.8 million children under the age of five who are severely malnourished. In 2011, Somalia suffered what is considered the worst famine the world has seen in the 21st century. A total of 260,000 people died. On that occasion, there were only three rainless monsoon seasons.

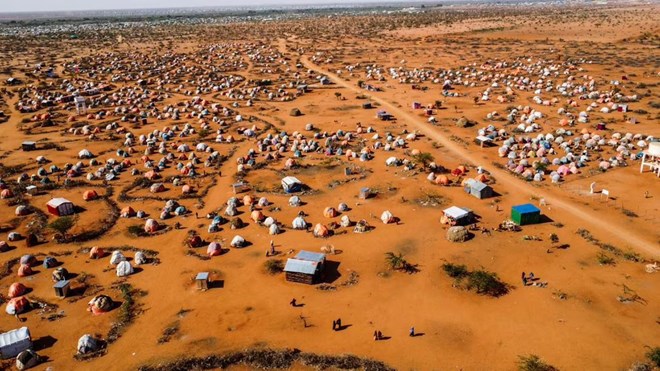

The Kaxaarey camp for internally displaced persons in Dolow, Somalia.

The Kaxaarey camp for internally displaced persons in Dolow, Somalia.

Experts are under no doubt that the situation is a consequence of climate change. Science shows that droughts and other extreme events, such as torrential rains, are now more frequent. The natural disaster cycle is narrowing. The phenomenon – provoked by the greenhouse gas emissions of developed countries - is taking its toll on Somalia despite the fact that it generates barely the level of CO₂ emissions produced by a tiny country like Andorra.

Lack of rainfall is also hitting other countries in the Horn of Africa hard, such as Kenya and Ethiopia. Hunger is spreading due to drought, while other global factors including supply chain problems resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic and the rising cost of food and fuel due to the war in Ukraine are exacerbating the problem. But in Somalia, there is an additional factor increasing the destructive potential of the crisis: the armed conflict that is ravaging the country.

Even in Dolow - an area controlled by government forces and relatively safe because of its proximity to the Ethiopian border, where security experts note that incursions by Al Shabaab terrorists rarely occur less than 20 miles away - reporters and aid workers move in vehicles escorted by pick-up trucks carrying four men armed with machine guns. With the roads infested with jihadists, the logistics of transporting humanitarian aid overland are complicated. “The context is very difficult,” says Elisha Kapalamula, a response manager for World Vision, an NGO that serves displacement camps in Dolow and other regions of the country. “Al Shabaab militiamen stop the trucks and keep the aid. If the government or aid organizations move the food, Al Shabaab confiscates it. And flying it in is very expensive. Local traders can move the food, so we have programs where, instead of giving the food directly to the displaced, they are given money to buy from local markets.”

Somalia’s 17 million inhabitants have for decades been living under the shadow of civil wars and fragile governments, which are being supported by the African Union and the United States to prevent the country from becoming a terrorist stronghold. It is a climate of instability that Al Shabaab - one of the most active and strongest offshoots of Al Qaeda - has been quick to exploit. The election of a new president last year, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, was followed by significant victories by government forces. But Al Shabaab militiamen, who are now even more unpredictable because they feel cornered, continue to spread terror in the capital and control large rural areas where they tax impoverished farmers, recruit their children and, in a display of unhinged cruelty, poison their water wells.

The areas under the yoke of Al Shabaab, which are equally drought-stricken but inaccessible to humanitarian organizations, complicate not only the delivery of aid but also the very ability to assess the scale of the crisis. That is one of the reasons why, despite the word being on everyone’s lips, the authorities have not yet officially declared a famine.

Famine declaration in Somalia

The UN Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), which monitors food security globally, said in a report published on December 13 that conditions in Somalia had not yet exceeded the threshold - IPC Phase 5 - necessary to declare a famine. But if the drought extends into spring, as experts anticipate, the IPC stated “more appalling outcomes are only temporarily averted.”

The IPC report estimated that there were 5.6 million Somalis experiencing “high levels of acute food insecurity” by December 2022, double the number at the beginning of last year. There is no available data on the number of deaths, but they are thought to number in the tens of thousands. Some experts argue that, in addition to the difficulty of accessing vast areas of the country, the IPC parameters are insufficient for the current crisis because the measurements are made over periods of a few months and are unsuited to droughts as prolonged as the current one.

Mohamud’s government is also proving reluctant to talk about famine. A declaration would provide an immediate injection of humanitarian aid and attract the attention of international donors who are now focusing their efforts on responding to other crises, such as the war in Ukraine. But by directing the international funding it currently receives - which makes up the bulk of its state budgets - to immediate relief efforts would drain funds from other long-term projects that the government considers of greater importance. Some international aid experts privately admit that in a scenario such as that afflicting Somalia, in which extreme weather events will become more frequent, it is more logical to invest in transformative programs in the long term. “The declaration of famine is in the end a political decision, one where the IPC has to agree with the government,” says World Vision’s Kapalamula. “Our goal is to try and ensure that declaration doesn’t have to be made. Now is the time to send resources, precisely to prevent that from happening.”

A child's foot peeks out from under a bed sheet at the hospital in Trócaire.ÁLVARO GARCÍA

There have been only been two famine declarations over the past decade: the 2011 famine in Somalia and the 2017 famine in South Sudan. But those who have lived through famine claim the situation now is even worse. “Throughout our history we have had big droughts, but this is totally different,” says Mohamed Hussen Abdi, head of trade for the local government, in his fortified office in downtown Dolow. “It is dragging on too long. We have learned from what has happened in recent years. We have to think, to find sustainable models so that our people can move forward. But right now, people lack food and water. They are starving. It is an emergency situation. We have to save lives first. As human beings, we cannot tolerate this.”