Friday July 19, 2024

by Kari Mutu

Photos and paintings revisit the colourful art and culture before civil war and rise of al Shabaab

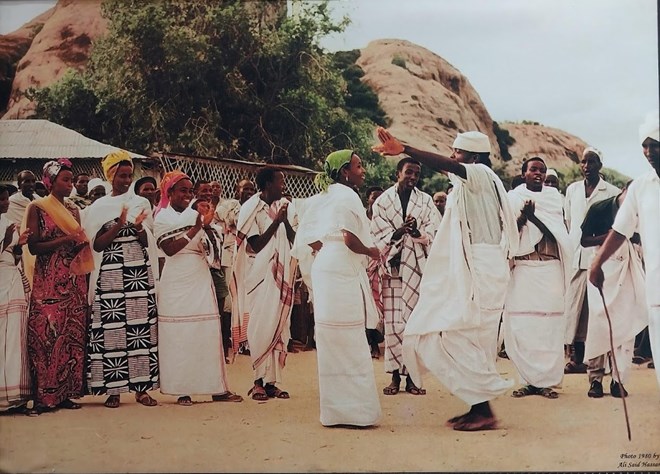

Folklore dance / Image: ALI SAID HASSAN AND GOLGOL GALLERY

An exhibition of Somali art and culture is showcasing the rich historical and cultural heritage of Somalia. The Somali Art and Cultural Exhibition at the Nairobi National Museum presents paintings and photography by renowned Somali artists active in the 70s and 80s. It is curated by Ali Hassan Said, the proprietor of Golgol Gallery, the first and last art gallery in Mogadishu, Somalia.

Hassan is a film studio and photojournalist who studied in Italy in the early 1970s. He travelled throughout different regions of Somalia, photographing everyday life, amassing a collection of 73,000 photo slides. Golgol Gallery opened in 1987 and in three years of operation, it had a collection of more than 1,100 mostly oil paintings and sculptures. Apart from the National Museum of Mogadishu, there was no other art gallery in Mogadishu.

When the regime of President Siad Barre was overthrown in 1991, Somalia was left without a national government for 13 years and plagued by clan-based conflict. During this time, the Golgol Gallery was destroyed, as was much of the infrastructure around the country. But Hassan managed to salvage a few paintings and brought them to Kenya. In 1999, he relocated to Germany, where he continued to preserve Somali documents and images. His work has been exhibited in Germany, Sweden and the UK.

The Golgol Gallery show has attracted much interest among the Somali community and others as it is a first of its kind in Kenya. Lydia Galavu, curator of contemporary art at the Nairobi Museum, said the exhibition is a great source of pride for Somalians, as they can identify with art that represents their community.

“But most importantly, local scenes reflecting on a people's history, culture and values resonate with everyone regardless of where we come from,” she said.

Naturally, there are paintings about historical conflict in Somalia, from colonial times to the present. State of Oppression, signed by Fanari, has a large flock of Somali blackhead sheep, tightly corralled in an enclosure guarded by one herder. It is an allegorical review of authoritarianism. “This person is weak, the door is open and the flock is very big, but nobody comes out because they accept the oppression,” Hassan said.

WINDOW INTO HISTORY

In the wide-ranging themes, the Golgol collection opens a refreshing window into Somali history, culture and ordinary life. The vital significance is captured in Water is Life, where a woman at the well is heartbroken because her water pot has broken. Photos of Mogadishu show what it looked like before the civil war: a thriving capital city. “Now it is completely destroyed,” Hassan said.

Unmarried Camel Herdsman by Cilmi Dheere depicts a young camel herder in white clothing and a red necklace surrounded by a group of his friends as he prepares to go and collect his bride.

Hassan tutored a number of young artists, teaching them to use locally available materials, such as handmade textiles from Somalia, paints made from indigenous plants and sesame oil. “To protect them from infrared and ultraviolet damage, we fixed the paint colours by brushing camel urine on them,” he said.

Folkore Dance, a photograph taken by Hassan in 1980, shows the happy scene of young men and women celebrating in the season of plenty after the rains. “Everything is growing, there is hope, so young people would have dances with ladies on one side, men on the other side and they made eyes at each other.”

Noticeable is the women’s cultural attire of long, colourful sleeveless dresses, headscarves and uncovered faces. “My mother and my sister were dressed like this before the revolution and before Wahhabism,” said Hassan, referring to al Shabaab extremists who favour the stricter Wahhabism style of Islam.

An abstract figurative painting signed 'Devios' speaks to the story of the African diaspora trying to assimilate abroad. “Africans think Europe is a paradise, everyone wants to go to Europe. But the society does not accept you, you have lost your culture and you are in the middle,” Hassan said.

The situation in Somalia is somewhat better than five years ago, he says, and in parts of Mogadishu, you can walk around peacefully. “But extremist al Shabaab is still a problem and they are against painting, art and pictures.”

Nevertheless, Hassan is determined to preserve his country’s artistic heritage and to repopularise art among Somalians. “Ninety per cent of society is not ready to understand the value of art. In Kenya, we have many talented artists but in Somalia, almost none.”

Hassan would like to display the artwork in other counties of Kenya and in Mogadishu. Ultimately, he hopes to create a permanent exhibition space that offers a historical record of Somalia through art, painting and photos. “These paintings are not for sale, not because I’m rich but because I want to exhibit them for the benefit of Somalis and for others to appreciate the culture.”