Tuesday October 22, 2024

By Jeffrey Meitrodt

If STEP Academy, a charter school with campuses in St. Paul and Burnsville, shuts down, it would be the largest charter school failure in Minnesota history.

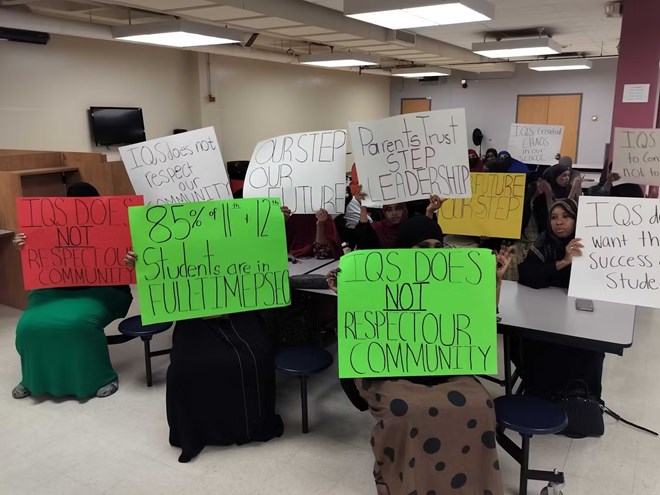

Parents attended a packed school board meeting at STEP Academy in St. Paul on Monday, holding signs protesting Innovative Quality Schools, which oversees the charter school. (Jeff Meitrodt)

The embattled leader of STEP Academy, one of Minnesota’s largest charter schools, agreed to resign, just a few days after he tried shifting the blame for the school’s financial crisis to the nonprofit that oversees the school for the state.

Staff members were told Monday that Mustafa Ibrahim, who has served as the top administrator of STEP since 2012, will resign. Two STEP board members, including chairman Abdulrazzaq Mursal, one of Ibrahim’s strongest supporters, also stepped down. Even though he was on the agenda, Ibrahim didn’t attend a crowded school board meeting Monday night.

It’s not clear if the leadership changes will help keep the doors open at STEP’s campuses in St. Paul and Burnsville, which are both bleeding cash and rapidly losing teachers.

At the Monday night meeting of the school’s board, parents learned STEP school’s deficit had grown from $800,000 at the beginning of the school year to $2.1 million, despite recent budget cuts that totaled $1.3 million. The sobering news prompted several families to swarm school officials when the board meeting ended.

Chief operations officer Paul Scanlon said he could not predict whether the school will survive.

“I’m not going to speculate,” Scanlon said, as he fielded questions from concerned parents. “We are doing everything we can to keep going. ... If we can reduce our costs, and come up with a payment plan, that will help us stay afloat.”

If STEP shuts down, it would be the largest charter school failure in Minnesota history. So far this year, nine of the 181 charters schools operating in the state at the beginning of 2024 have closed, the most since the first charter school failure in 1996, state records show.

The controversy over STEP’s management has led to divisions among parents and staff. On Monday night, parents packed STEP’s St. Paul cafeteria with those who appeared to support STEP leaders holding up a range of posters with sayings like ”Parents trust STEP leadership” and ”IQS created CHAOS in our school.” Some parents and employees have defended the school and its academic program which has boasted graduation rates as high as 100% in recent years. However, another segment of teachers have strongly criticized administrators.

At STEP, up to nine teachers have told co-workers that they will soon be leaving the school, and other departures may be in the works.

“The main concern now is whether we can keep our current staff members,” said Katie Royseth, who has worked as an educational assistant at STEP for four years. “If we cannot, it would be near impossible to continue.”

Rahima Ahmed, a teacher at STEP who resigned from the board last week, was more optimistic.

STEP Academy’s expansion into Burnsville in 2022 depleted the school’s financial reserves. The nonprofit that oversees STEP has now recommended that STEP consider closing this campus or its St. Paul school in order to survive its financial crisis. (Jeffrey Meitrodt/The Minnesota Star Tribune)

“I am deeply confident that STEP Academy will continue to grow and thrive in the years to come,” Ahmed said in a written response to questions. “While I remain dedicated to the school’s success, I believe it’s time to step back and allow fresh voices and new perspectives to help shape the path forward.”

STEP Academy, which serves 783 students at its campuses in St. Paul and Burnsville, has been repeatedly cited for contract violations by Innovative Quality Schools (IQS), the nonprofit that oversees the school as an authorizer for the Minnesota Department of Education.

In an Oct. 4 letter, IQS warned STEP leaders the school’s finances are in “an incredibly fragile state.” To survive, IQS said in the letter, STEP must take immediate and significant action, such as closing one of its two campuses.

A week later, after IQS accused school leaders of failing to make necessary adjustments, the nonprofit threatened to terminate STEP’s contract in a follow-up letter. Such actions have typically led to the closure of charter schools because they are not allowed to operate without an authorizer.

Some staff members who attended Monday’s board meeting said they were disappointed by the accusations against IQS.

“I don’t feel it is true,” said Katie Gogo, the school’s special education coordinator. “I think IQS wants to keep the school open, but they also realize how much of a deficit we’re in.”

Parents at Monday’s meeting told board members they dreaded the prospect of having to find a new school for their children in the middle of the year.

“Most people came to this school because we believed and we trusted in Dr. Ibrahim,” said Aliyo Jama, whose three children attend STEP Academy.

In a five-page statement to the Minnesota Star Tribune, Ibrahim blamed STEP’s financial problems on IQS. He said the nonprofit has abused its power by creating “unnecessary barriers and distractions” that have destabilized the school. Ibrahim accused IQS of attempting to “wrest control” of the school and replace its Black leaders with “hand-picked white professionals.”

“The financial challenges we face are directly linked to IQS’s incessant meddling in our decision-making processes and erosion of our autonomy,” Ibrahim said in the statement. “Their deliberate and discriminatory practices have consumed our time and resources, diverting our focus from core educational priorities.”

IQS first cited STEP’s board for weak oversight in 2019, saying it failed to respond when Ibrahim repeatedly engaged in “improper management practices.”

The situation didn’t reach crisis levels, however, until the costs of the school’s 2022 expansion into Burnsville wiped out STEP’s financial reserves. Its fund balance, the most critical indicator of a charter school’s financial health, fell from $2.7 million in 2022 to $54,461 in 2023, state records show.

In response to Ibrahim’s allegations, IQS said in a statement that its repeated interventions were aimed at ensuring the school operates within state guidelines and lives up to the promises made in its contract with the nonprofit.

“It is unfortunate that Dr. Ibrahim has made unfounded claims of racial bias,” IQS Board Chair Steve Kelley said in a statement. “He is wrong. IQS and its leadership team have acted professionally and impartially.”